The Swiss lady from the local wine shop told me that the following varietal was quite old and native to Rheinhessen. Although I'd never heard of the grape, I was somewhat sceptical of her claim. Lo and behold, when I researched online at home I found out that Würzer is actually a crossing of Müller-Thurgau and Gewürztraminer, courtesy of Georg Scheu (he of Scheurebe fame) in 1932. Nothing that old or native about it at all, despite the fact that around 40 of the 60 or so hectares of vineyard it accounts for in Germany were admittedly planted in Rheinhessen. Here instead is the bastard love child of two grapes everyone loves to hate. What could possibly go wrong?

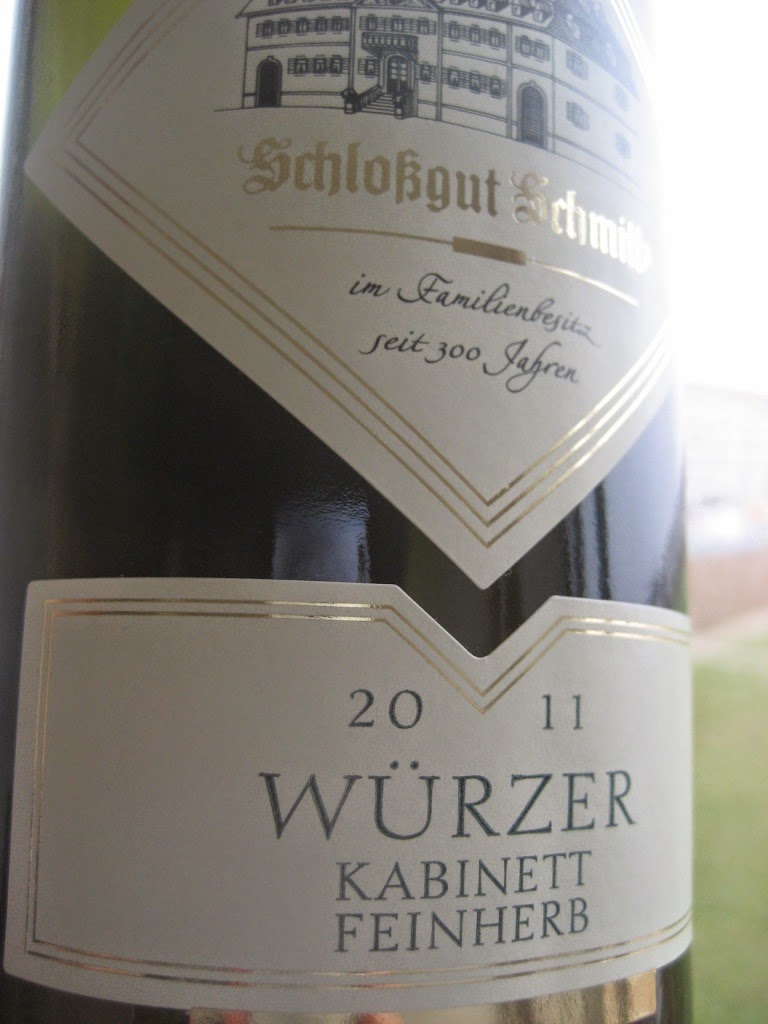

The Swiss lady from the local wine shop told me that the following varietal was quite old and native to Rheinhessen. Although I'd never heard of the grape, I was somewhat sceptical of her claim. Lo and behold, when I researched online at home I found out that Würzer is actually a crossing of Müller-Thurgau and Gewürztraminer, courtesy of Georg Scheu (he of Scheurebe fame) in 1932. Nothing that old or native about it at all, despite the fact that around 40 of the 60 or so hectares of vineyard it accounts for in Germany were admittedly planted in Rheinhessen. Here instead is the bastard love child of two grapes everyone loves to hate. What could possibly go wrong?Schlossgut Schmitt, Guntersblumer Kreuz Kapelle Würzer Kabinett feinherb 2011, Rheinhessen

In truth, the wine turns out to be a revelation. Almost a golden yellow colour. The main theme on the nose is starfruit. It is a bitter kind of citric zing that maybe tends more to lime on the second day. On the periphery, we also have mildly honeyed, waxy notes hinting at oncoming maturity as well as a somewhat rubbery whiff (think warm squash balls or the inner tubing of your bike tyres). Starfruit continues on the palate, followed by a suggestion of something honey-related. Then the acidity attacks with short, sharp precision. Were it not for its slightly bitter starfruit characteristic, you might be forgiven for mistaking this wine as a Riesling if you tasted it blind. In fact, it feels a bit like Riesling on steroids. It may lack a certain depth and grace, and the finish is dry and straightforward, but it made a great pairing with the sweet and sour dish I concocted.

To be honest, I was expecting something spicy and sweetish, but this wine is bright, alert, refreshing and a more-than-worthwhile discovery. Judging by its keen, bitter acidity, I would say that the off-dry idiom suits it to a tee. The alcohol level is a mere 9.5 percent. Price: CHF 14.90.